Health and Education

The survey highlights significant disparities in the healthcare services accessed by migrants during their time in Thailand. While 54 percent of documented migrants have utilised a public hospital, a mere 12 percent of undocumented migrants have done so. Strikingly, 68 percent of undocumented migrants have not sought any healthcare services at all, compared to 39 percent of documented migrants.

One possible explanation could be the relatively short duration many migrants have spent in Thailand combined with their younger average age, particularly among undocumented migrants. This might mean they have had less need for healthcare services. Additionally, for various ailments and concerns, migrants might prefer consulting pharmacies rather than healthcare providers. Nevertheless, the vast difference in healthcare utilisation between documented and undocumented migrants suggests that factors beyond mere lack of need are at play.

In terms of healthcare coverage, Bangkok boasts the highest overall coverage, with over 50 percent of migrants in the area having access to some form of healthcare providers.

The utilisation of public hospitals is notably highest in both Bangkok and Samut Prakarn. A primary reason for these regional disparities in public hospital access is the system where many migrants are registered to a specific hospital upon receiving their work permit. If they relocate for work, they may lose access to the hospital they were initially registered with.

As for community health centres, including those run by NGOs, the highest access rates are observed in Tak (17 percent), Bangkok (16 percent), Chiang Mai (11 percent), and Chiang Rai (10 percent).

There are significant differences in challenges faced by documented and undocumented migrants in accessing healthcare. Whilst 32 percent of documented migrants reported no challenges, this number drops to just 22 percent for undocumented migrants. The most prevalent issue for undocumented migrants is the lack of proper documentation, which often precludes them from using public hospitals without a passport or the requisite papers. Both documented and undocumented migrants also reported distance or transport issues as common challenges, likely because they work in areas far from the hospitals where they are registered. Only 18 percent mentioned high costs as an issue, and a mere 2 percent reported poor treatment, reflecting the general quality of healthcare in Thailand.

Discussions with representatives from the World Health Organisation (WHO) highlighted regularisation as the fundamental issue affecting access to healthcare. In addition to this central issue, geographical healthcare coverage poses another significant challenge, as confirmed by the survey data. According to WHO representatives, even with proper social security measures in place, migrants often find it difficult to access healthcare services due to distance and the limitations of their health insurance policies. More comprehensive health insurance is often readily available at a low cost, but lack of awareness means that migrants frequently do not take advantage of these options.

Other challenges are related to family planning and care, a point also highlighted by another NGO, the Baan Dek Foundation. There is limited awareness in migrant communities regarding family planning. When migrants do have children, especially if undocumented, it becomes difficult to secure adequate healthcare coverage for them, given that children are often more susceptible to illness. To mitigate against these challenges, migrants should be permitted to seek advice and care from health centres, clinics, and pharmacies regardless of their documentation status, instead of being restricted to the facilities where they have been previously registered.

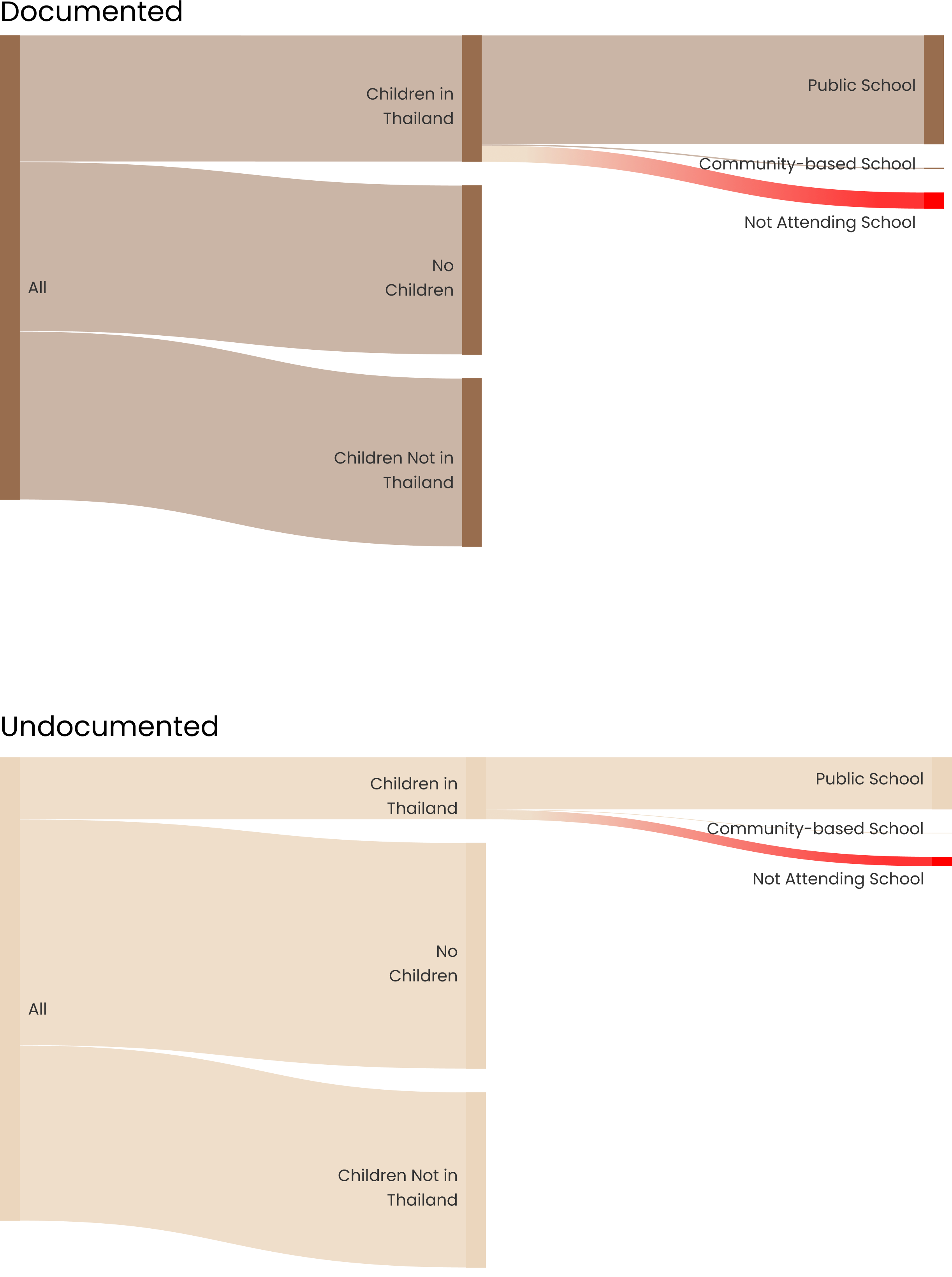

Out of the total sample surveyed, 59 percent of migrants reported having children. Among those with children, 37 percent had bought their children with them to Thailand. The percentage differed between documented and undocumented migrants; 43 percent of documented migrants, had their children with them in Thailand whereas this was true for only 30 percent of undocumented males and 23 percent of undocumented females. When it comes to education, the survey revealed that among those who had children, 86 percent of documented migrants’ children attended public school. This is slightly higher than the 84 percent of undocumented migrants’ children who also attended public schools. A total of 15 percent of undocumented migrant children did not attend school compared to 13 percent of documented migrant children.